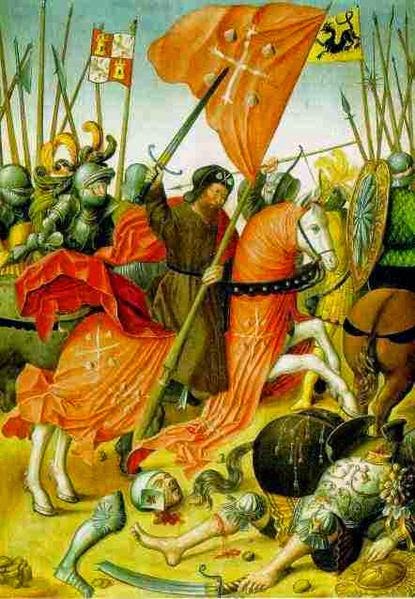

The

Apostle of Christ and Holy War. A painting attributed to the Circle of Juan de

Flandes (c.1510–20) of Saint James fighting the Moors. He is shown carrying the

banner of the Spanish military order bearing his name, the Order of Santiago.

The incongruity of this transformation of one of Jesus’s disciples into a

warrior saint escaped most medieval observers.

In Spain, as in the Baltic, crusading was

secondary or complementary to secular considerations and wider association of

Christian conquest and holy war. A decade before the First Crusade, Alphonso VI

of Castile had characterized his capture of Toledo from the Moors in 1085 ‘with

Christ as my leader’ as a restoration of Christian territory and the recreation

of ‘a holy place’. It is not entirely clear how far the explicit religiosity of

twelfth-century accounts of earlier campaigns against the Moors in Spain

reflected the assimilation of crusading formulae, an older tradition of holy

war or a separate local development. While defence and restoration of Christian

lands matched the new rhetoric of the Jerusalem war, indigenous writers and

religious leaders transformed the Iberian patronal saint, the Apostle James the

Great, Santiago, into a ‘knight of Christ’ and heavenly intercessor for the success

of Christian warfare. Such promotion of a distinctive pan-Iberian war cult

helped local rulers retain ownership of their campaigns even when enjoying

papal crusade privileges while at the same time reinforcing Christian

solidarity. St James, an international saint through his shrine at Compostella,

did not become the exclusive preserve of any one Iberian kingdom, his cult

sustaining the political ideologies of all of them. The same was generally true

of the half dozen Iberian Military Orders founded in the second half of the

twelfth century, including one dedicated to St James.

Crusading in Spain adopted a local flavour.

The great warrior kings of the thirteenth century, Ferdinand III of Castile

(1217–52) and James I of Aragon (1213–76), rolled back the Muslim frontier

self-consciously in the name of God and each flirted with carrying the fight

beyond Iberia, to Africa or Palestine. Yet neither found the commitment that

led their contemporary Louis IX of France to the Nile. Although some conquests,

such as the capture of Cordoba by Ferdinand III in 1236, were accompanied by

religious gestures of restoration and purification familiar from the eastern

crusades, and in places, as at Seville (captured 1247), foreign Christian

settlers were recruited, much of the Reconquista involved negotiation and

accommodation of the religious and civil liberties of the conquered: James I

‘the Conqueror’ of Aragon’s annexation of Mallorca (1229) and Valencia (1238),

and Ferdinand III’s conquest of Murcia (1243). Christian complaints about the

calls of the muezzin persisted in some areas for centuries. Although suffering

from the problems of being ruled by an elite with separate laws and religion,

Muslims under Christian rule, the mudejars, and Jews and converts – conversos (Jewish

converts to Christianity) and Moriscos (Muslim converts) – were a feature of

Spanish life until the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when a

recrudescence of a manufactured neo-crusading religious militancy led to the

imposition of intolerant Christian uniformity under the Catholic monarchs

Ferdinand II of Aragon (1479–1516) and Isabella of Castile (1474–1504),

coinciding with the final expulsion of the Moorish rulers from Granada (1492). This

new identification of a crusading mission, which persisted under Charles V and

Philip II, depended as heavily on recasting Castile, in particular, as itself a

new Holy Land with a providential world mission as it did on genuine Aragonese

crusading traditions. In turn, this spawned a myth of the crusading reconquista

and the providential identity and destiny of Catholic Spain later insidiously

expropriated by General Franco and his fascist apologists, academic as well as

political.

The fate of Peter II of Aragon (1196–1213),

father of James the Conqueror, reveals the nuances and contradictions in the

Iberian experience. The twelfth-century invasion of Spain by the Almohads,

Muslim puritans from North Africa, had placed the Christian advances of the

previous century in jeopardy. In 1212, a large international crusader host

combined with Iberian kings to resist. Before confronting the Almohad forces at

Las Navas de Tolosa, most of the French contingents abandoned Peter and the

kings of Castile and Navarre, partly over disagreements over the local rulers’

leniency towards defeated Muslim garrisons, a frontier pragmatism that, as in

Palestine, struck the French as scandalous. They also did not care for the

heat. The subsequent Christian victory became, as a result, almost wholly a

Spanish triumph, a useful detail in the later projection of Spanish destiny.

Fourteenth months later Peter was defeated and killed at the battle of Muret in

Languedoc by an army of French crusaders led by the church’s champion, Simon de

Montfort, testimony to the political cross-currents upon the surface of which

crusading bobbed, and the impossibility of divorcing ‘crusade’ history from its

secular context.

After the conquests, new (or in propaganda

terms restored) sacred and secular landscapes were created, from converting

mosques to churches to changing Arabic place names. In some areas, notably in

Castile, immigrant settlement from further north was encouraged. Elsewhere, the

pre-conquest social and religious structures felt only modest immediate impact.

It may be significant of a decline in frontier militarism that after 1300, the

cult of Santiago faded before that of the Virgin Mary. Nonetheless, the holy

war tradition, in its crusading wrapping, persisted amongst the knightly and

noble classes, available to those engaged in wars against infidels, Muslim or

heathen, a living cultural force as well as a stereotype. While his captains

were observing West Africans outside the straitjacket of crusading aesthetics,

the Portuguese prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) fervently embraced crusading

aspirations and campaigned in North Africa. As late as 1578, a Portuguese king,

Sebastian, at the head of an international force armed with indulgences and

papal legates, fought and died in battle against the Muslims of Morocco. The

penetration of Latin Christendom into the islands of the eastern Atlantic in

the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries attracted crusading grants for the

dilatio, or extension, of Christendom. The Iberian tradition ensured a

sympathetic hearing for the Genoese crusade enthusiast Christopher Columbus. It

formed one strand in the conceptual justification for the conquest of the

Americas and, more tenuously, in the mentality of the slave trade which some

saw as a vehicle for expanding Christianity. This was made possible by the

idea, popular by c.1500, that Spain itself (however imagined) was a holy land,

its Christian inhabitants new Israelites, tempered and proved in the fire of

the Reconquista, championing God’s cause whether against infidels outside

Christendom or heretics within.

No comments:

Post a Comment